By Rabbi Dovid Markel

Anyone who has even the most perfunctory knowledge of Judaism knows that the Torah obligates that man treat animals with the utmost care.

Of the many mitzvos in which this is expressed is the following:

The Torah states[1], “When an ox or a sheep or a goat, is born, it shall remain under its mother for seven days, and from the eighth day onwards, it shall be accepted as a sacrifice for a fire offering to the Lord.”

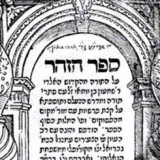

Maimonides[2] understands that this verse expresses a positive commandment, that a sacrifice is only accepted when the animal is at least eight days old.

In Maimonides’s words: “the 60th mitzvah is that we are commanded that every animal we sacrifice must be no less than eight days old. This is known as being m’chusar z’man b’gufo (itself lacking time)… The expression, “After the eighth day, it shall be acceptable,” implies that beforehand it is not acceptable. This clearly indicates a prohibition against bringing the sacrifice before the proper time.”

This mitzvah expresses the tremendous compassion that G-d has for all of His creatures, as the verse[3] states, “The Lord is good to all, and His mercies are on all His works.” For, while many cultures have ignored the proper treatment of animals, Judaism mandates that man treat both man and beast with the utmost care.

Scholarly Jewish texts have explained the reasoning behind this law in various ways[4]. Of these, there are two that stand out which express the consideration that the Torah demands that one have on all creatures:

1) The Torah has compassion for the mother of the animal. It therefore mandates that one not remove the child from it before it had a chance to enjoy its company prior to it being sacrificed[5].

2) It is an exceedingly cruel trait to remove the newborn beast from its mother. The Torah does not wish that man develop cruel character traits and therefore mandates that man wait eight days before taking the animal as a sacrifice[6].

We see, therefore, that man must have compassion on the beast and is prohibited from expressing cruelty to all of G-d’s creatures.

[1] Vayikra 22:27

[2] Sefer HaMitzvos, Ase, 60; Mishna Torah, Isurei Mizbeiach 3:9

[3] Tehillim 145:9

[4] See Yalkut Yitzchak, Mitzvah 294

[5] Yalkut Yitzchak, Mitzvah 294. It would seem that if this mitzvah is to express mercy on animals, it would be even more merciful not to offer the animal as a sacrifice to begin with. This, though, is not the case. A) Sacrificing the animal is the only way that man can find forgiveness and is mercy on man. B) The sacrifice uplifts the animal as well. The animal is not only slaughtered for man’s sake but the animal itself gains. The verse (Tehillim 36:7) states, “You save both man and beast, O Lord,” which expresses that both man and beast are uplifted through sacrifice.

[6] Tzror HaMor, Vayikra 22:27

[1] Vayikra, 22:27

[2] Sefer HaMitzvos, Ase, 60, Mishna Torah, Isurei Mizbeiach, 3:9

[3] Tehillim, 145:9

[4] See Yalkut Yitzchak, Mitzvah 294

[5] Yalkut Yitzchak, Mitzvah 294. It would seem that if this mitzvah is to express mercy on animals that it would be even more merciful not to offer the animal as a sacrifice to begin with. This though is not the case. Sacrificing the animal A) is the only way that man can find forgiveness and is mercy on man. B) It uplifts the animal as well. The animal is not only slaughtered for man’s sake but the animal itself gains. The verse (Tehillim, 36:7) states “You save both man and beast, O Lord,” which expresses that both man and beast are uplifted through sacrifice.

[6] Tzror HaMor, Vayikra, 22:27