To view as Pdf click here

By Rabbi Dovid Markel

Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for his classifying morality into two distinct groups—slave-morality and master-morality.

He argued that Judaic values were a subversion against natural noble values and indeed is a moral system that is only fit for slaves.

The slave resents the power that his master yields over him and creates new definitions of morality that are reactions to the negative feelings toward his master.

The success of “slave-morality,” according to Nietzsche, is that it ultimately subjugated its master and enforced a perverse sense of ethics on the strong and noble. Instead of praising strength, it admired humility; instead of celebrating the conquering of one’s enemies, it championed showing mercy to them.

The Jews, in his words, caused a transvaluation in morality in their statement[1]:

“The wretched alone are the good; the poor, the impotent, the lowly alone are good; only the sufferers, the needy, the sick, the ugly are pious only they are godly; them alone blessedness awaits — but ye, the proud and potent, ye are for aye and evermore the wicked, the cruel, the lustful, the insatiable, the godless; ye will also be, to all eternity, the unblessed, the cursed, and the damned.”

Ultimately, he called for a reevaluation of values and a return to master-morality, where strength should be venerated instead of denigrated and humility should be scorned instead of idolized.

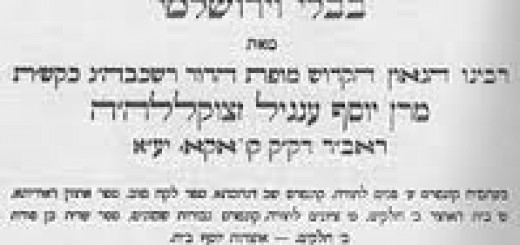

This was not the first time that western-values were at odds with Judaic ones. The Talmud[2] tells of an encounter between the Sages of Israel and the great conqueror, Alexander the Great, which is in many ways reminiscent of Nietzsche’s complaint against Judaism.

“He said to them: ‘Who is called wise?’ They replied: ‘Who is wise? He who discerns what is about to come to pass.’ He said to them: ‘Who is called a mighty man?’ They replied: ‘Who is a mighty man? He who subdues his evil passions.’ He said to them: ‘Who is called a rich man?’ They replied: ‘Who is rich? He who rejoices in his lot.’ He said to them: ‘What shall a man do to live?’ They replied: ‘Let him mortify himself.’ ‘What should a man do to kill himself?’ They replied: ‘Let him keep himself alive.[3]’”

The answers postulated by the Hebrew sages were all counterintuitive: Wisdom, strength and wealth are not measured by an outside barometer—as man relates to the world around him—but by an internal one.

However, there is a deep truth in the statement of the Rabbis:

According to western values, a person created alone would not ever be able to be defined as wise, mighty or wealthy, as he has no one to compare himself to. The definitions then, are never true to the individual but only as they relate to others.

What’s more, is that when using the indicator of the other, one will never be wise, mighty or wealthy; as compared to the individual who may have more than oneself, a person is but a fool, weak and a pauper.

Classifying oneself according to the other will always leave the person wanting more.

It was perhaps this important piece of advice that the Sages wished to impart to Alexander the Great. Possibly, they were telling him that no matter how many countries he conquers, plunders and learns from, he will never be satisfied unless he looks inwards instead of outwards. He must conquer himself rather than conquering the world.

In the clash of ideas and ideals, the Hebrews were telling the Greeks, that contrary to normative thinking—which sees Israel as weak and Greece as powerful—in reality, the opposite was true. As, genuine virtue was beyond what the Greek mind was able to grasp.

The same is true with regard to life and death: It is not the pursuit of greatness that helps a person live, but humility and scorning pride. Indulgence is not the point of life but the antithesis of it.

Gods vs. G-d

The story is told of two Jews speaking together about a third older Jew. The individual turns to the other and asks: “So, do you know my friend Moshe?” “Moshe?” says his companion, “I can’t think of any Moshe.”

“Well,” he continues, trying to jog his memory, “Moshe the hunchback.” When he is met with a blank stare, he continues, “Moshe, the one who is blind in one eye.” Still not getting any sign of recognition, he says, “You know, the Moshe who is missing a leg.”

“Ah, that Moshe,” says his friend with a smile on his face. “He’s mamesh a sheine yid! (He is such a beautiful Jew!)”

For a Jew, beauty is not defined in tangible, quantifiable descriptions that fit into neat boxes, but there is instead an abstract, indiscernible beauty of the soul that is ever-present, expressive in the entirety of the person, yet transcendent and beyond him.

This is the focal difference between the pagan gods and ideals—worshiped by Alexander and venerated by Nietzsche—and the true G-d of Israel.

The Greek gods were easily defined. They are mighty, beautiful, swift, wise and any number of decisive descriptions. Whereas the G-d of Israel—to differentiate—is limitless and undefinable. As Maimondes explains—and this sentiment is echoed by others—any description that we apply to G-d is really a negation of a negative trait and not truly a positive description of G-d.[4]

The Greek citizen or emperor, in the spirit of imitatio dei, emulates their gods. They too attempt to be mini-gods, exemplifying strength, wealth, beauty and wisdom.

What they perhaps failed to realize is the deficiency of their limited, finite values and gods. No matter how strong one can become, there will always be limits. When the character of one’s person or the values of one’s empire is built upon definable values, it eventually comes to an end. It reaches its zenith but eventually its quantifiable strength wanes—until all that is left is a distant memory of a glorious past.

True strength is not merely the power expressed by Oskar Schindler in the quote, “Power is when we have every justification to kill, and we don’t.” Authentic might is about completely transcending the very definition of power and reaching humility.

For, as long we continue to define ourselves in quantifiable parameters, we are unable to be a conduit for G-d. Concerning the haughty the Talmud[5] declares, that G-d says, “I and he cannot both dwell in the world.”

The reason being, that the more a person defines himself, the less room there is for G-d to be expressive. When a person is utterly humble, it is there that the infinite presence of G-d can be expressed.

This is expressed in the following Talmudic statement:[6]

“Come and see that the manner of the Holy One, blessed be He, is not like the manner of human beings. The manner of human beings is for the lofty to take notice of the lofty and not of the lowly; but the manner of the Holy One, blessed be He, is not so. He is lofty and He takes notice of the lowly, as it is said:[7] For though the Lord be high, yet hath He respect unto the lowly.”

For, the lowlier a person feels, the less they are negating G-d’s presence. It is this strength of humility that makes a person a receptacle for an infinite G-d that Nietzsche failed to see.

True Power

It is this type of strength that is typified in the leadership of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

While venerated by followers the world over, he is a person whom extremely nothing is known about. Though there have been many valiant efforts to try and document his life, he remains larger than life.

Though he spoke for thousands of recorded hours, one would be hard-pressed to find instances where he ever uses the word “I.”

Notwithstanding—or perhaps because—of his ultimate humility, he had the courage and power to transform the world. The overwhelming power of the Rebbe’s personality rather came because he was not present.

The courage that he had to conquer the world with Jewish values against impossible probabilities, was because the strength was not his own—but was rather G-d’s. Because he was invisible, the infinite power of G-d and his Torah completely permeated his identity and person, giving him the leadership powers that transcended quantifiable definitions and is still ever present in his followers.

Indeed, it is this humility that is the ultimate power of the Jewish people and the secret to their survival through millennia of persecution, exile and terrors.

It is not strength in the normative definition that brings a person to sacrifice his life for his beliefs, but it is rather humility. It is not courage that makes a Jew stand up against a world that hates him and provides the tenacity to rebuild Judaism against unsurmountable odds—but a boundless trust in G-d.

It is perhaps because of the power of humility—as such that it helps us be a conduit for an infinite G-d—that the Torah time and again reminds us that we are slaves.

We should not be deluded into placing pagan values of quantifiable values on a pedestal—as being finite and definable, they are here today and gone tomorrow. Not in such values can the Jewish people become an eternal people.

Only with humility can we transcend the definitions of time and space, becoming an everlasting people, forever bound with an eternal G-d.

Eventually, this infinite expression of G-dliess will be completely expressed with the coming of Moshiach—speedily in our time!

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality. Essay 1.

[2] Tamid 32a.

[3] Let him indulge in pleasures (Rashi, ad loc).

[4] Guide to the Perplexed, 1:58

[5] Sota, 5a.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Tehillim 138:6.