By Rabbi Dovid Markel

When the Talmud (Berachos 28b) describes the passing of the sage, Rabbi Eliezer, it records an interesting episode:

“Our Rabbis taught: When R. Eliezer fell ill, his disciples went in to visit him. They said to him: ‘Master, teach us the paths of life so that we may, through them, win the life of the future world.’ He said to them: ‘Be solicitous for the honor of your colleagues, and keep your children from higayon, and set them between the knees of scholars, and when you pray, know before whom you are standing and in this way you will win the future world.’”

In the moments before R. Eliezer was to leave this world, and in his final advice to his students of how to merit the World to Come, he teaches that rather than having your children become drawn into higayon, they should instead be sat down before scholars.

While there are various explanations as to the exact definition of the term higayon, in general they are split into two categories: that higayon is derived from the word speech or from the word thinking.

Although the two things seem very different, the commonality between the two definitions is that in both there is a danger of emptiness rather than content. Instead of this lack of content ,one should ensure that their children study the true wisdom of our sages.

In both explanations, it is about setting priorities in one’s child’s education:

According to various commentators, what is being prescribed here is that one should ensure that their children not study Greek logic and secular philosophy.[1]

They see the danger of studying logic before the child knows the difference between good and evil. First must be ingrained in the child the difference between good and evil—as taught by our holy sages—only then, when the child has grown up, can he perhaps begin to study logic to enhance his ability in Torah.

Others see this as a prohibition against teaching children the art of speaking.[2] The danger inherent in this is the same as above. When a person has the art of sophistry, knowing how to manipulate language and use syllogisms to their advantage without actually have anything to say, it can be extremely dangerous.

Pure logic—without revelation of Torah—will not help the child know right from wrong and beautiful speech. While outwardly giving the appearance of brilliance—it can in fact be completely shallow and empty.

Just as Rabbi Eliezer’s advice was true in his day, it is essential today as well. All too often we raise our children to be smart but to have no wisdom, to be eloquent speakers but have nothing to say.

Not only is this a mistake that they remain empty, but more so, it carries with it the danger expressed by Yirmiyahu (4:22) “They are wise to do evil, but they know not to do good.” For often, a little wisdom can be more dangerous than a lot of simplicity.

Instead, we should be careful to sit our children “between the knees of scholars.” Only then will we ensure that they positively affect the world and win a place in the world to come.

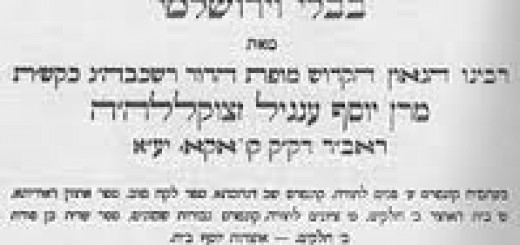

[1] Anaf Yosef, See as well Rabbi Yaakov Anatoli in the preface to his translation of Ibn-Rushd’s book on logic.

[2] Maharal, Netivot Olam, Avoda 2